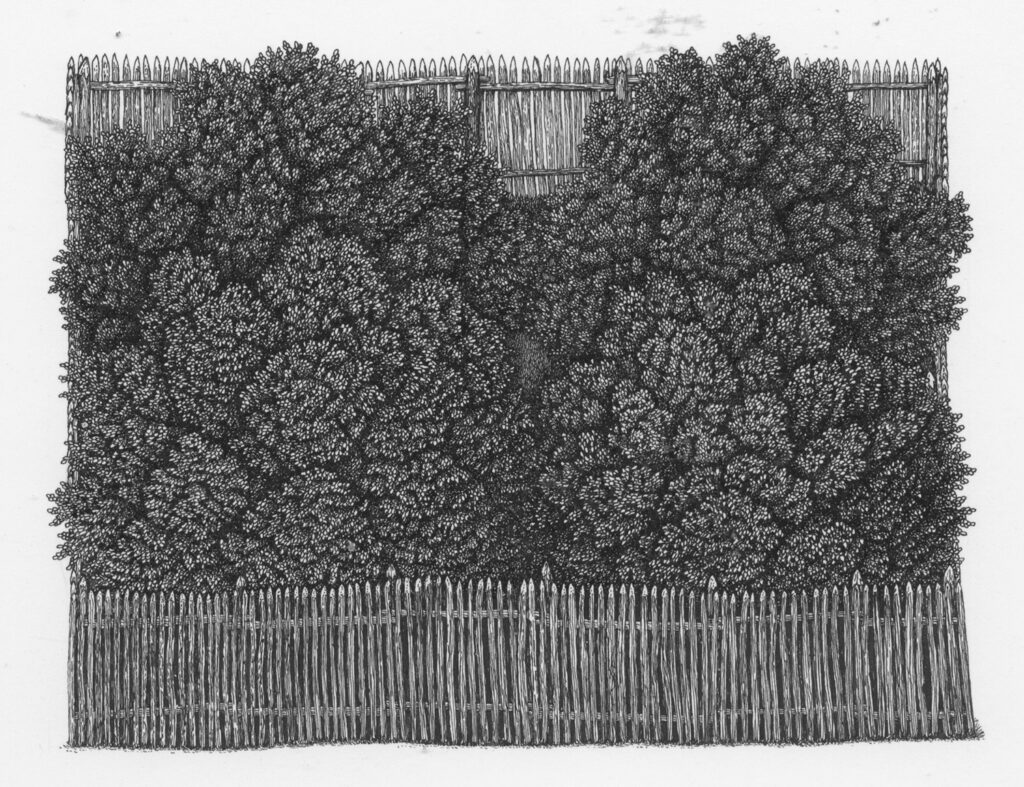

In times when handwriting was, more permanently than the clay and graphite lead encased in cedar wood called pencil, the pervasive phisical means of words before Fleet street print them in soot on pulp to poison the fish’n chips, the tiniest of contraptions only the English produced the material for, the steel quill, emulating what had been the only possible reason people would hunt crows, their feathers. So much so that a Joseph Gillott, maker of the best metal quills in the world, would come to fund a hefty share of the Tate Gallery institution’s, at second place behind only the sugar behemoth.

1 – The Art Of The Quill.

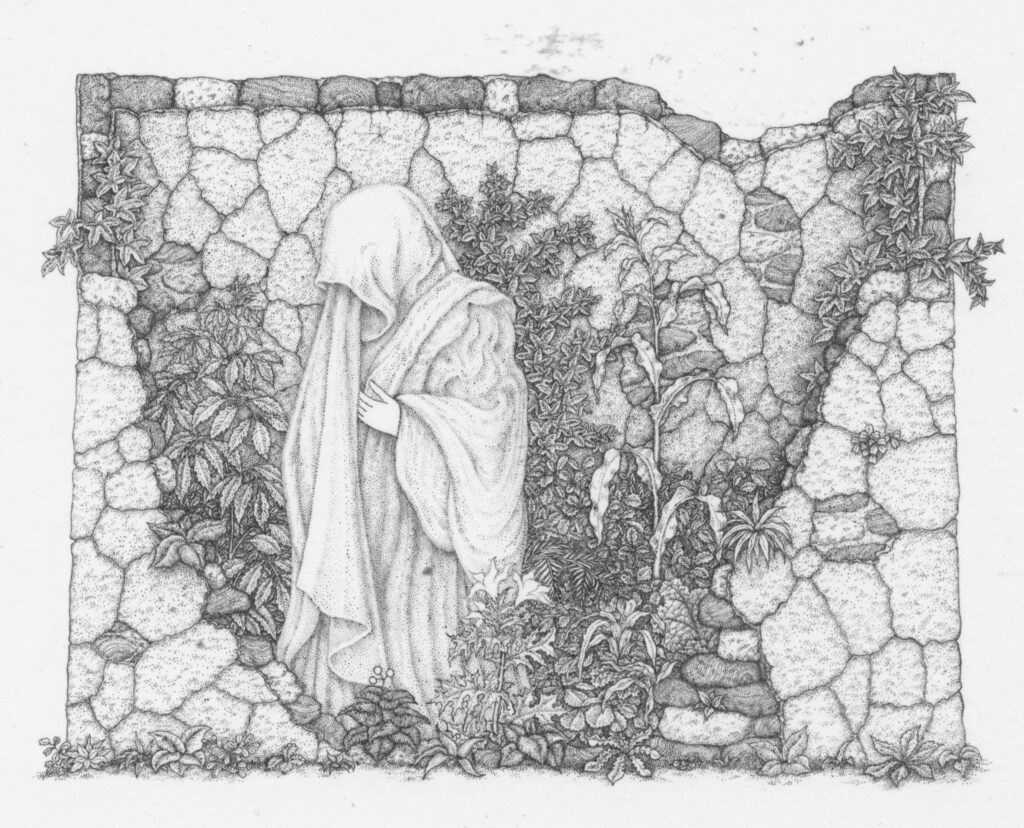

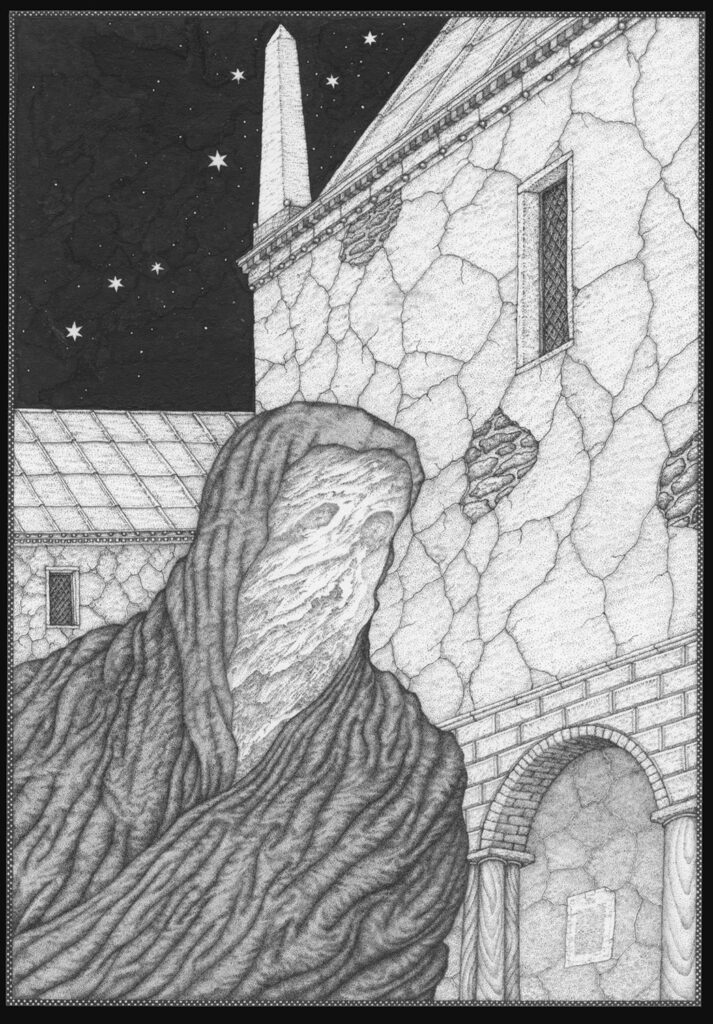

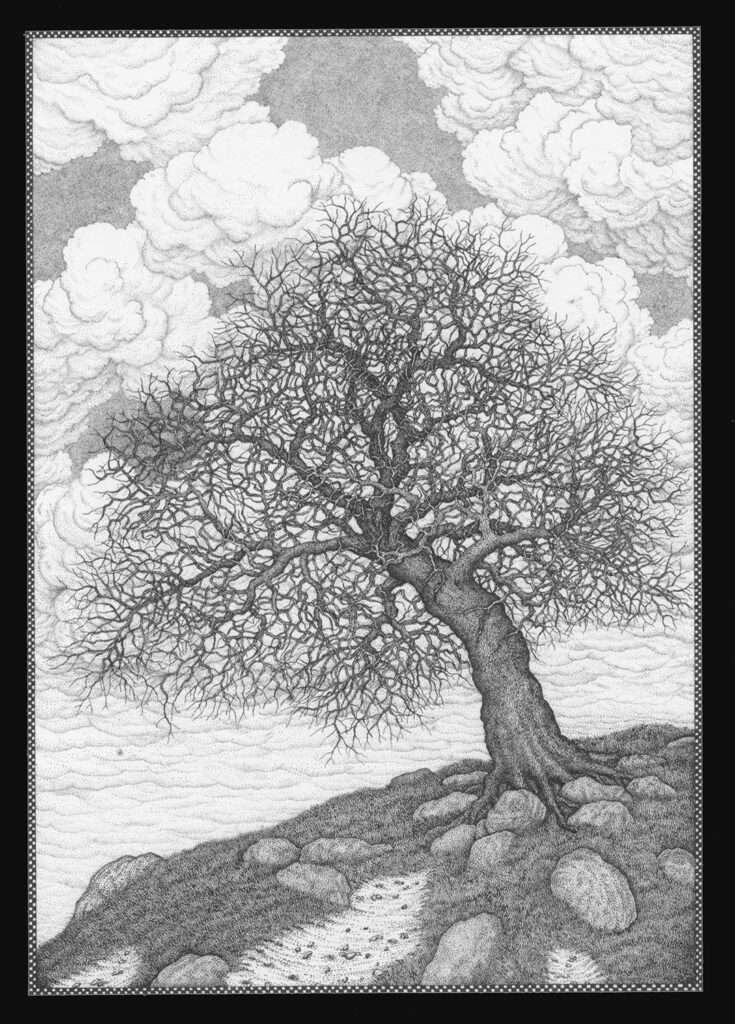

Hence, in the heydays when, across the café “La Palette” stood a sympathetic emporium of arts supplies where they would let me rummage into the vast drawers —I never was a shoplifter— where I found my first Gillott crow quills and the adapted wood holder. I am altogether self-taught, dropped out of high school, and was deeply impressed by some Grand Palais theme shows about Baudelaire, the British Romantics, and matters they seem to overlook these days. There, I met crushing giants, in my scope, who had not met any audience in their time, the likes of “chien-caillou” Rodolphe Bresdin, who had drawn, with the steel quill on the lithographic Solnhofen limestone slab, the endlessly fascinating “Bon Samaritain”.

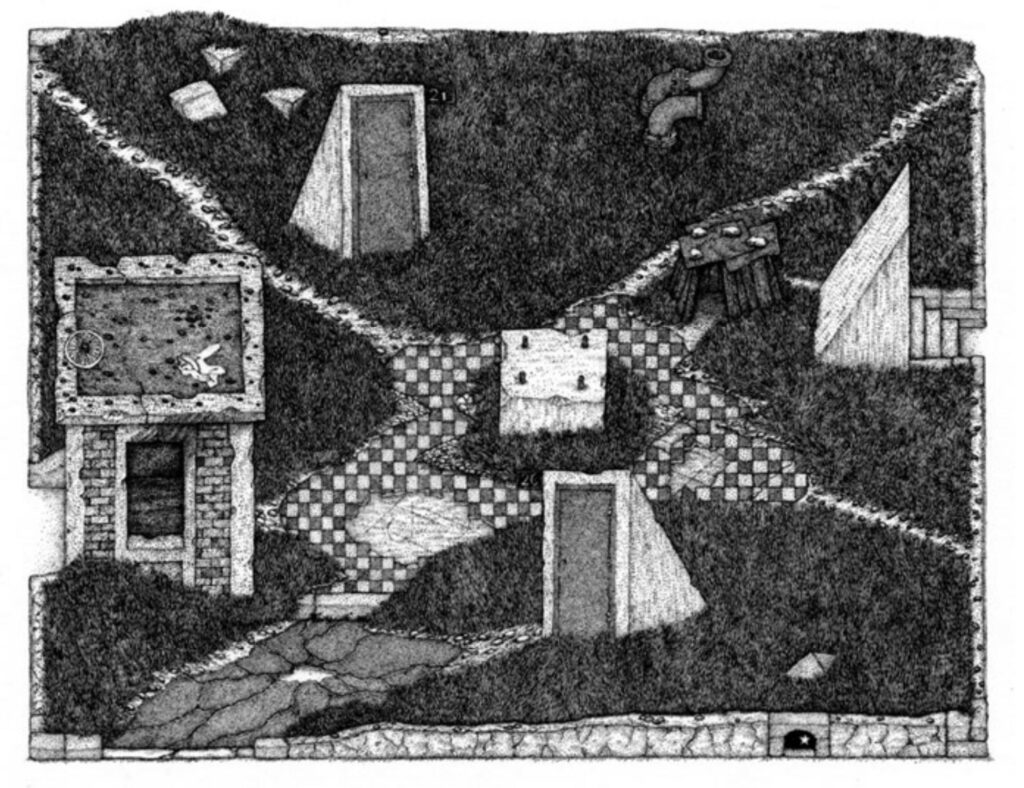

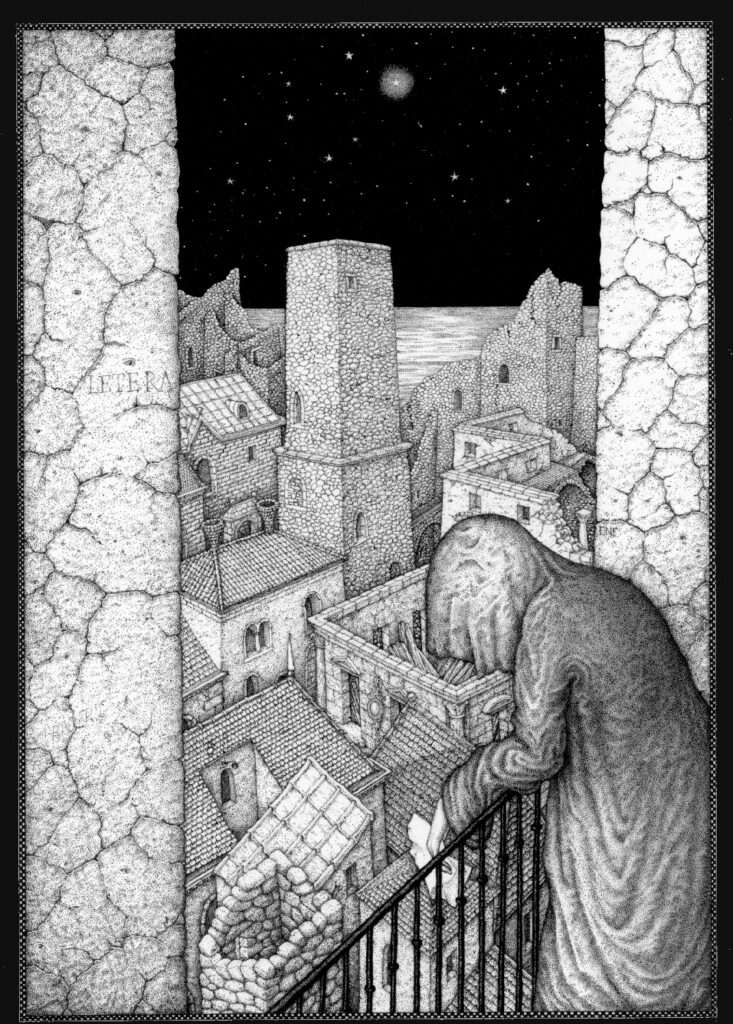

Later, an old schooldays acquaintance of mine whose father was a surrealist painter and owned an Art and Essay cinema where he also hosted important collective shows, let me haunt the parages of the then still vibrant group. But life necessities and influences led me to struggle making a living in commercial art, for which I was not exactly gifted and I will not disclose here.

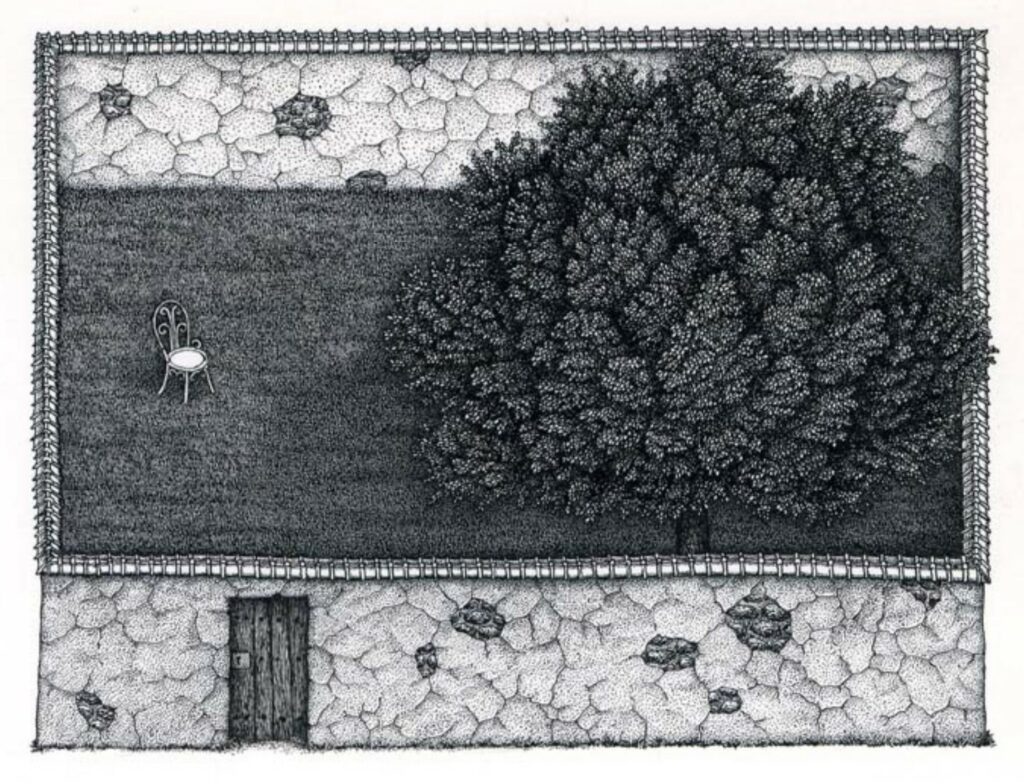

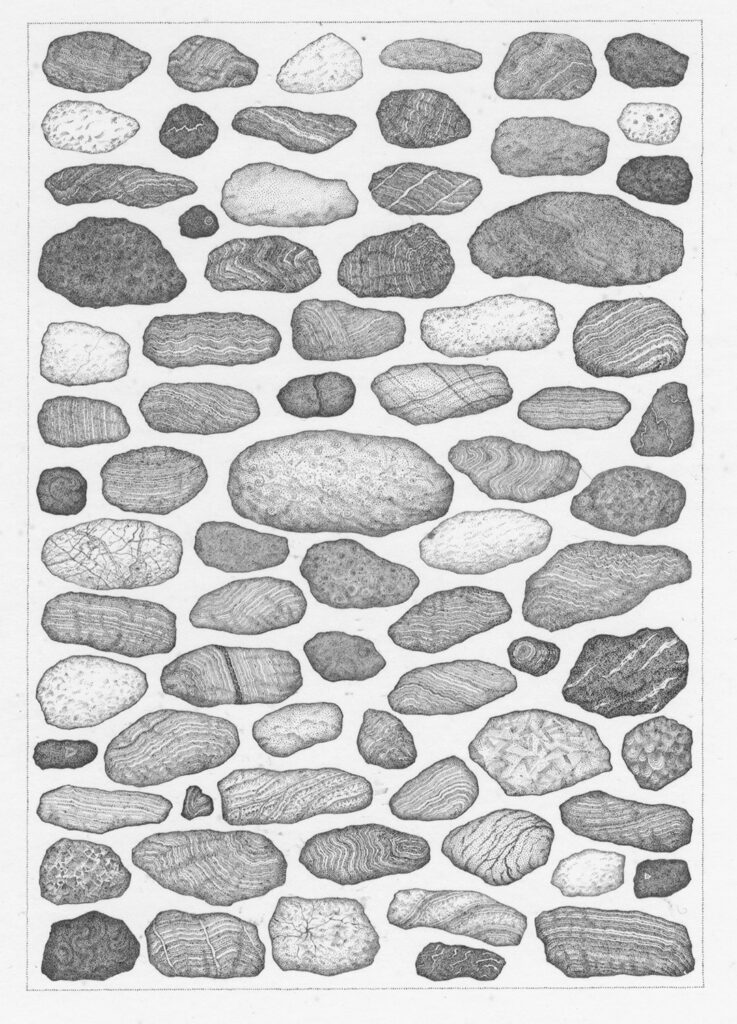

Amidst a discombobulated percourse i which my prime artistic hunches had been wasted, but the constant love of my wife, came this unforeseen incite from a friend who officiated as art director of a now defunct financial weekly, and who commissionned me black and white illustrations for a special on earth land as an investment.

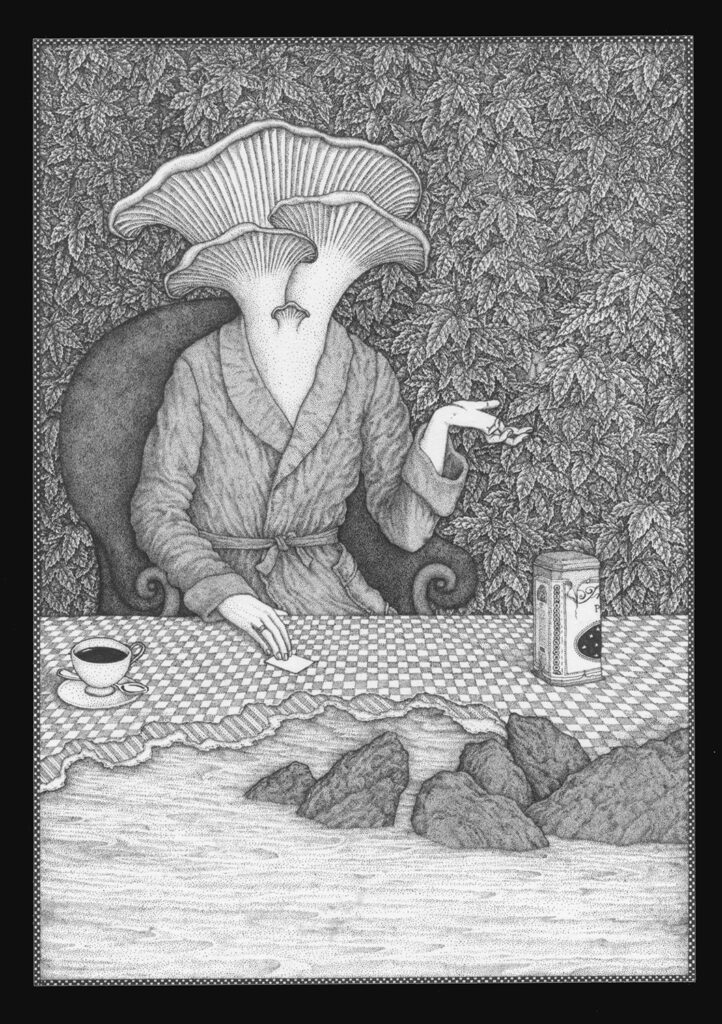

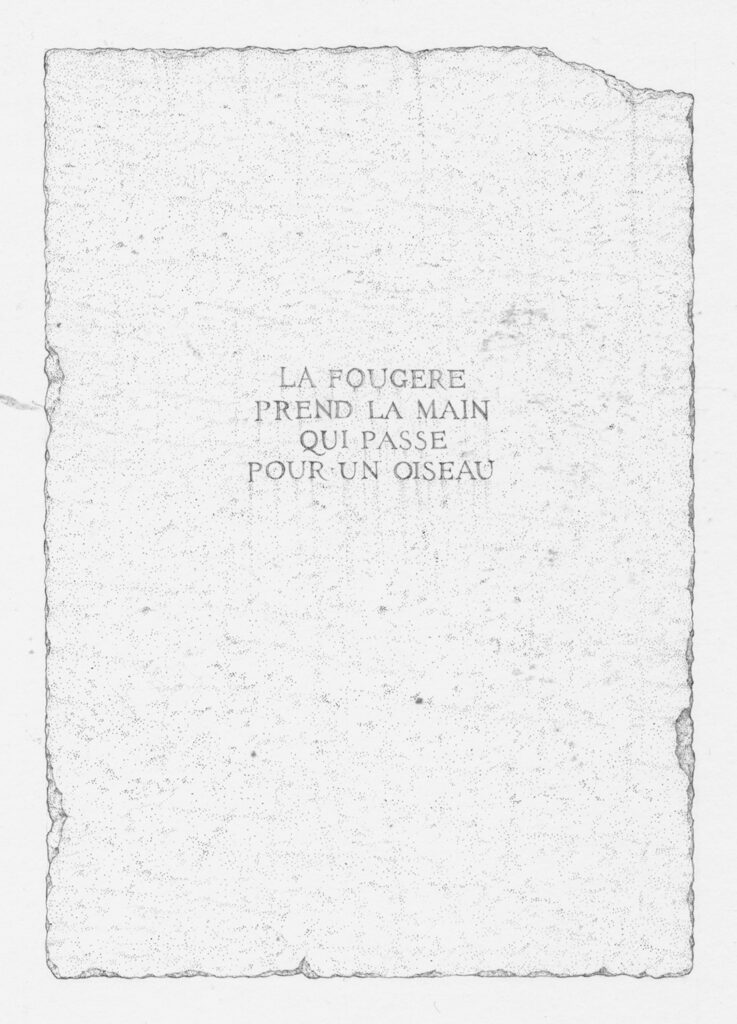

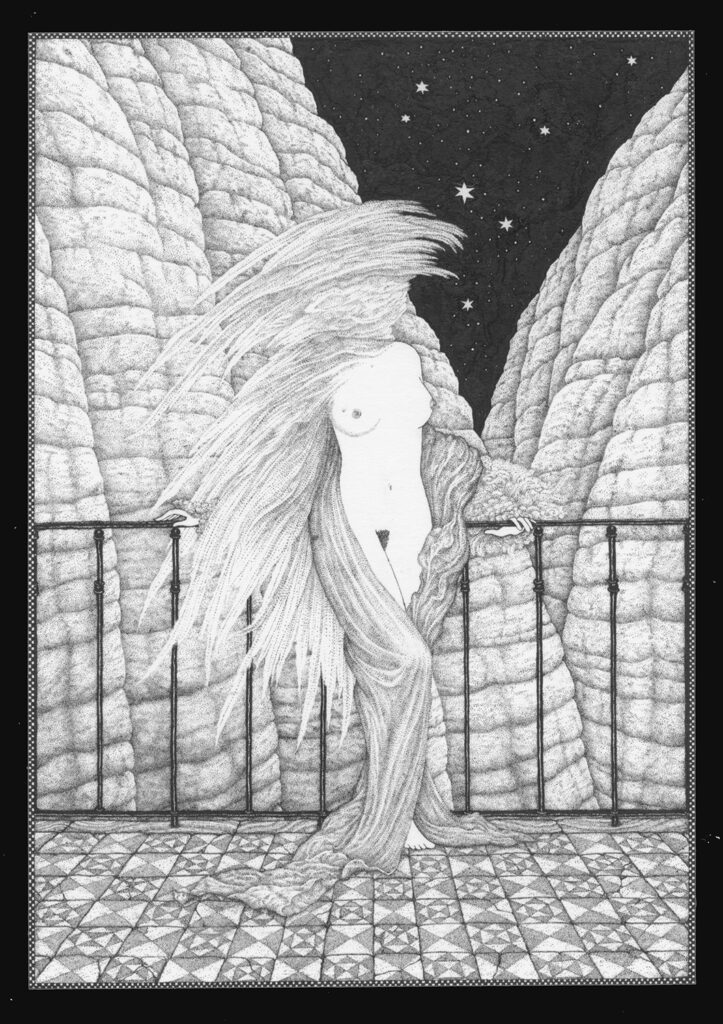

It might have not been worth hailing, but it cranked in years of pen drawing with the ghostly project of an illustrated poetry book that never was because the only persons I could confide about it at Gallimard’s had died.

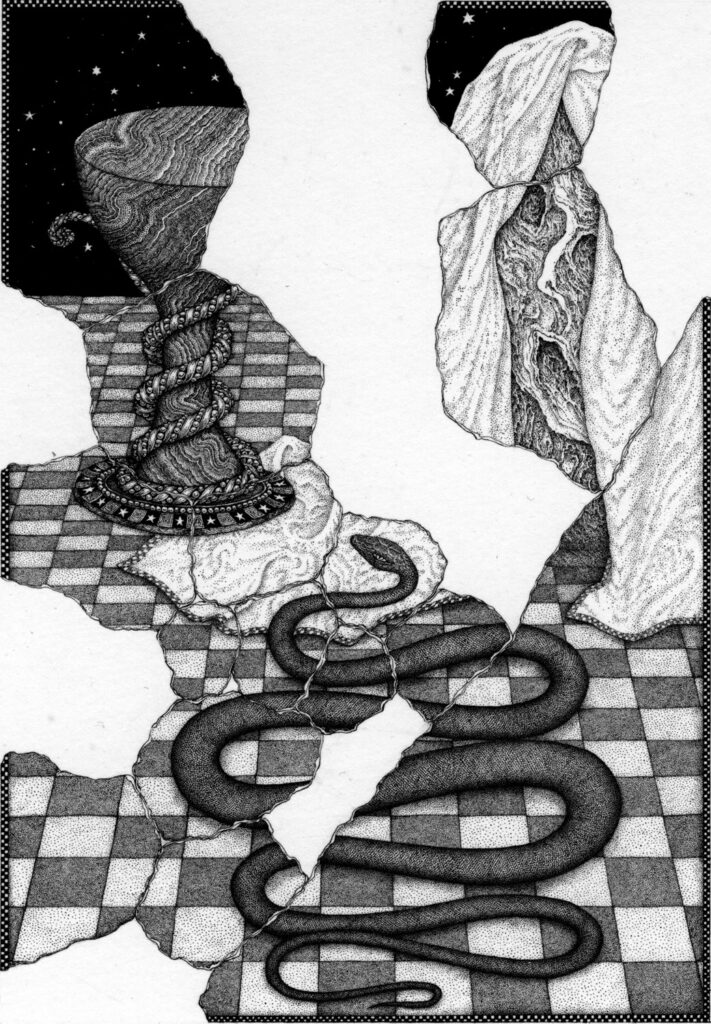

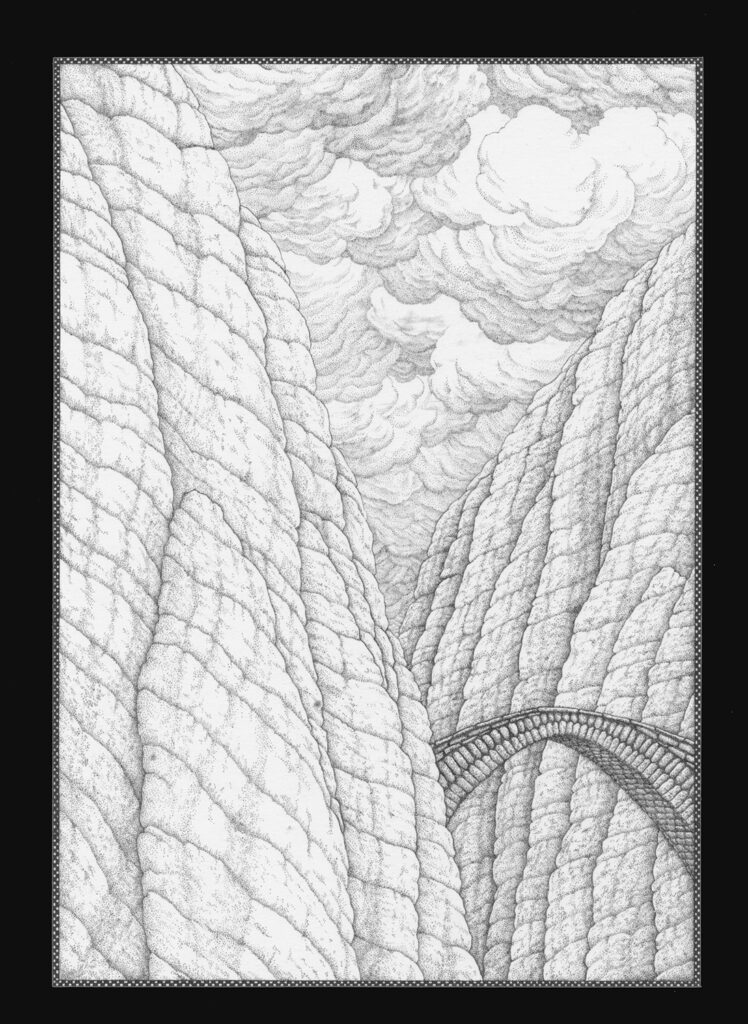

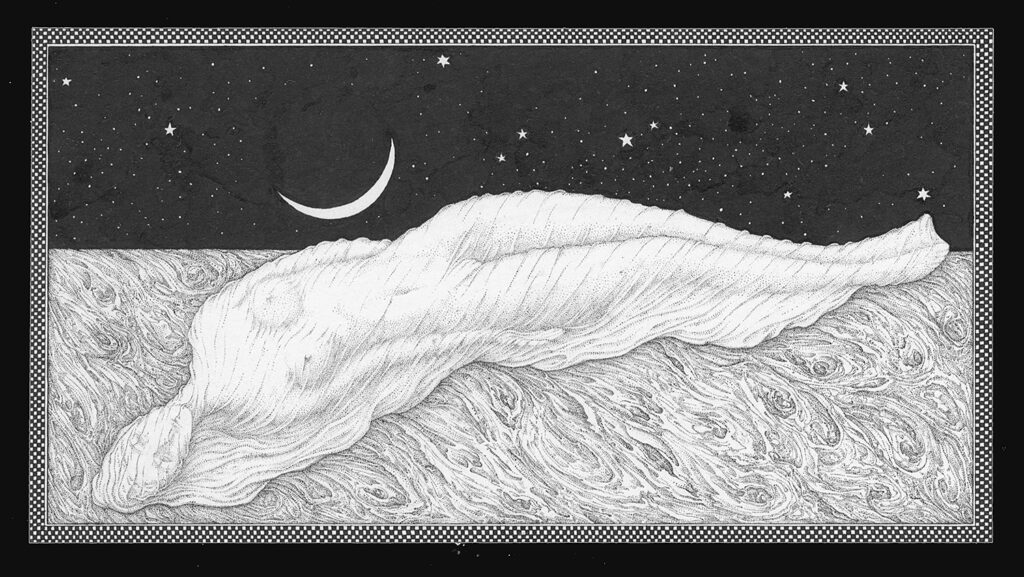

All this time-consuming labour of love stumbled, beyond the illogical sequence of its presentation, upon the limitations of reproduction techniques. Lithography as such had disappeared, and I couldn’t invent myself as an etcher, go and learn the craft in some workshop. Vaguely jaded, but supported by family, I made another attempt using the watercolour technique that did not garner much interest in my artistic acquaintances. And otherly, the once fruitful advertising illustration market was harshly waning anyhow.

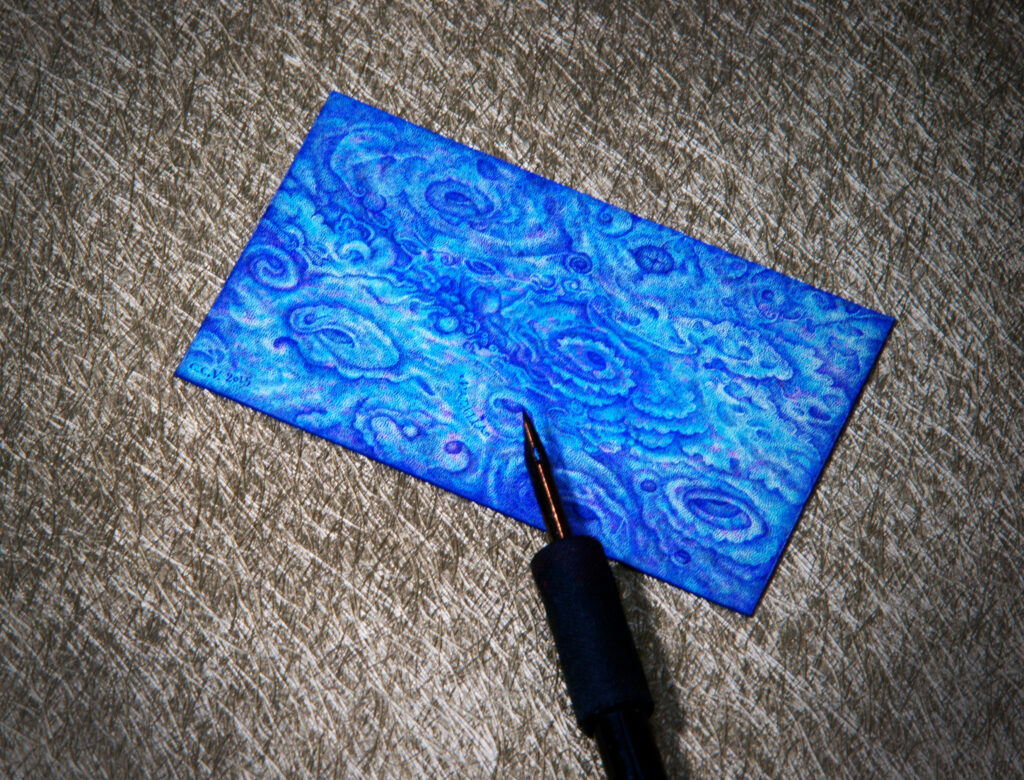

I lost the taste for oddly figurative subject matters I had no training for. I found myself better with unleashed textures, once described as organic abstraction, naively trying to reverse the Frenhofer effect, so to speak.